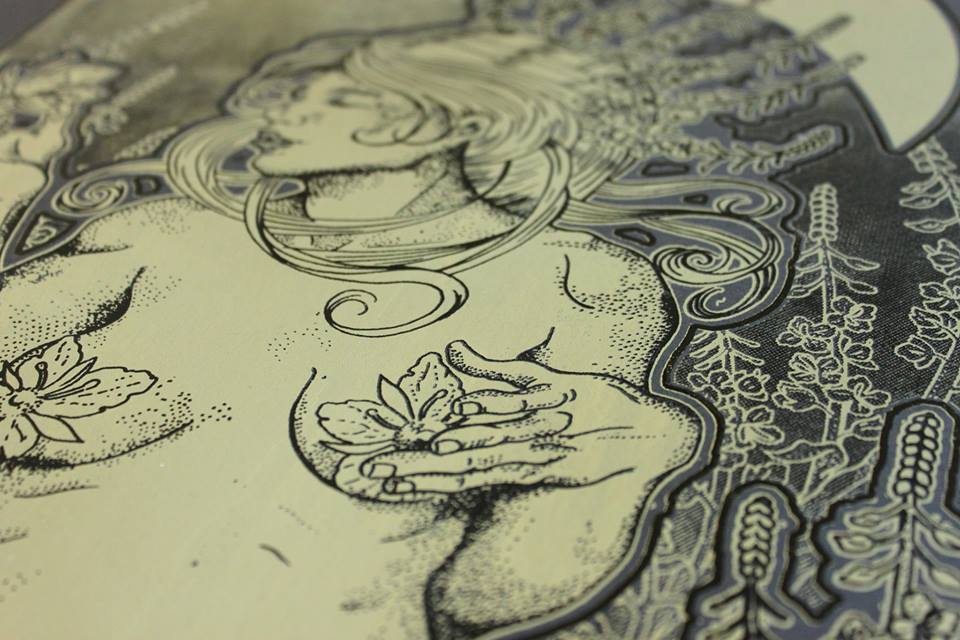

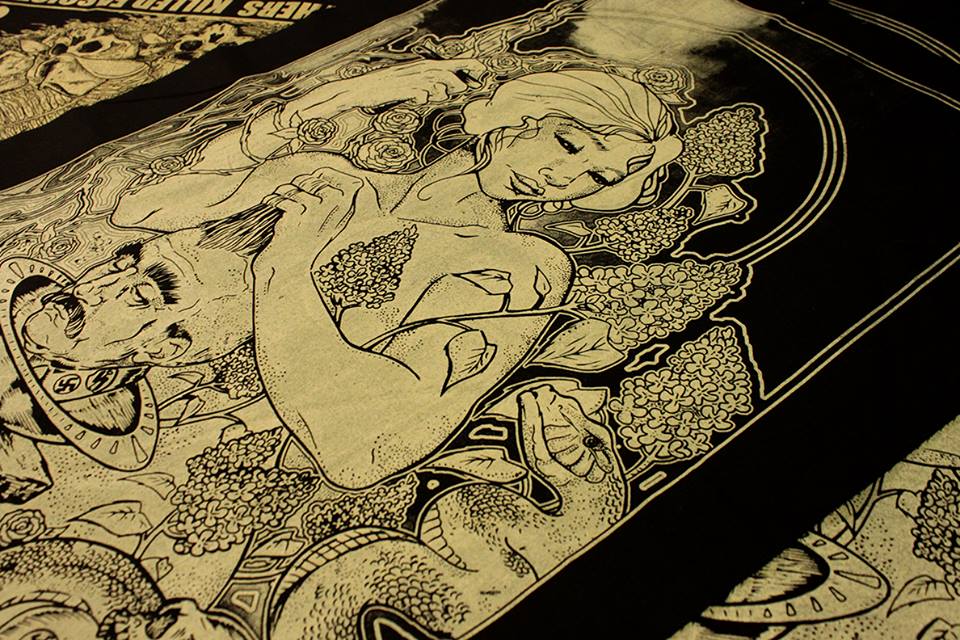

N.O. Bonzo is a muralist and graffiti artist in Portland, OR who has been using her platform to articulate a feminist, anti-fascist message. It’s Going Down published an interview with N.O. Bonzo in 2016, and 1312 Press took that interview and formatted it into a zine in an effort to push a feminist and anti-fascist message in the graffiti community, a scene that is at times over-run with misogyny and rape culture. Prints and t-shirts by N.O. Bonzo can be purchased here.

* * *

There are few contemporary artists which combine both illegal graffiti with intense attention to detail, feminine images and characters, and hard hitting political content and messaging quite like N.o. Bonzo, based out of Portland, OR. Having already made a strong name for themselves both within the graffiti and street art world and within anarchist circles, and with continuing ventures into books and print making, we wanted to catch up with N.o. Bonzo to get their thoughts on everything from Portlandia to eco-fascism.

How did you get involved in illegal art? Could you always draw really well when you were younger, or is it something that you had to work on? What was the process like physically moving onto the streets? Can you describe the early years?

I became involved when I was 12, and all the kids in the neighborhood in Tampa I had just moved to were writing on everything and listening to punk and hip-hop. I was pasting political posters and scrambling to put up your pretty typical teenage punk rhetoric on everything, while at home I was working on becoming an animator or comic artist.

I drew everyday, and would spend hours just practicing lines and forms anywhere I ended up, it ended up becoming my total all encompassing coping technique. Today I still have a pretty high amount of anxiety if I’m without a sketchbook. It wasn’t till I moved to Indianapolis and saw folks like Sacred of Fab crew or Grawer, people just doing really extraordinary work, that I felt pushed to try and put my own work up and try and make that work really beautiful.

I was still getting messy, running around putting up posters about Indy’s anti-houseless campaigns and what not, but spent the other half of the week starting to experiment with these super colorful oversized wheatpastes that told stories. It just grew from there as I tried to make each piece larger, more complex, started mixing my own paint, trying to tell bigger stories.

You’re based in Portland now. Is Portland where you come to prominence in the graffiti world? What was that process like?

My dad was from PDX, so I spent a lot of time up here visiting and falling in love with the city. I spent most of my early life moving around a lot, being in a bunch of radically different places on the East Coast, SouthEast, and Midwest. One day, my sister became pregnant, dad committed suicide, my mom was stuck in another state, so permanent relocation for fam.

Ha! I’m not sure if prominence is a word that I’ll ever really think about, I think I’m still one of those people that your friends introduce you to. A lot of people have seen it, immediately recognize it, but I’m almost never signing my name to it. PDX was where I finally started to make things in a way that was hard to ignore. I had finally developed a lot of the skills I wanted to have to be doing these huge things I had been dreaming of. I’m still pushing that skill set to be able to make the things I dream about now. I think the work I started producing out here became a lot more personal and narrative, and people connect with it in much more intimate ways. Connecting in ways that are a lot different from most experiences which happen in a city.

Your art has always featured female bodied people at the center of it. What drew you to center this aspect so prominently in your art? How do you find people react to it?

I think a lot of us who are drawn to doing this work, do so because we in some way have these overwhelming personal experiences and dominant cultural narratives telling us we don’t matter and no one values us. I came from a lot of trauma and domestic violence, and pretty early on saw the state’s unwillingness to intervene in that violence, and the communities’ (at that time) inability or lack of concern around disrupting it.

A lot of the organizing and work I do nowadays surrounds community intervention and support around domestic and sexual violence. Moving around so much, I ended up early on in a town where the folks I met and lived with were experiencing racial, economic, domestic, and/or environmental violence pretty intensely. A lot of the people in my peer group didn’t have a lot of experience being told we mattered to anyone, and writing your name on the wall, is a big way to disrupt that.

Most of my pieces are highly personal in ways that for me are easiest to communicate visually. I’m working things out. I draw the people I do because you don’t often see women portrayed in anything other than highly consumable and passive objects. The only place you’re ever going to find folks who are telling their own stories in city space, is with the traditional and modern mural artists, graff writers, and street artists. I want to see folks who experience marginalization getting up and taking space in completely unapologetic and challenging ways in whatever feels best for them. For me the space that I’m drawn to challenge those dominant narratives, is on city property.

People react to it in a bunch of different ways considering their particular orientation. For the city, they want to buff it in less than twelve hours. For a lot of folks, they want to either cover the nipples, tear it down, or tell me about “nice tits.” And then there’s the folks who write poems on them, search half the city to take photos of them, will trade me these amazing zines they make, or just sit by them for a little bit.

Graffiti has always been really male dominated. What’s the reaction been to your art? Have you gotten negative responses to it? What has that been like?

I feel like that reaction, but not the male dominance, has been changing.

For most folks, a lot of them thought I was a dude due to the scale of a lot of my work, but that’s changed as I’ve been more outspoken on women and trans visibility in the streets. When I was first in PDX, I was having a lot of really directed misogyny, rape threats, people spraying “c**t” on my pieces, and telling me these lines about how “It’s not sexism, it’s because you’re a b***h.” Pretty much your standard run of the mill MRA nonsense.

Then you get this other side of that noise, where dude’s have unhealthy fixations and boundaries and send you some creepy “nice guy” manifestos about their fantasy relationship with you, a stranger they have of course never met. I think any person who isn’t a cis-dude, can share these experiences with each other, and that’s why we not only love seeing each other up, but need to. It’s just like constant background radiation.

I would actually dream of every time I got to visit the Bay and just kick it with all of the amazing folks down there, who honestly, were, my main source of artistic validation. I was lucky here to have amazing supportive folks who would help me process, laugh it off, and go put up the next big piece. I can never give enough love to CircleFace for being the most amazing person through all that.

“I get these messages sometimes from the most unbelievable sweeties who wanna connect. I had these two sisters send me a video of them hula-hooping to show how they were little bad-asses unafraid of patriarchy and I cried for like ten minutes.”

I feel there’s been a shift in PDX, I’m older, been around for longer, people have come and gone, and I could never dream of any of that happening now within the street scene. Its become a much more welcoming space for other voices, a see a lot of women and queer folks up now. I’m just talking about the street scene, elsewhere is all a different story.

Has your work encouraged more non-males to get involved in graffiti through your activities? If so, can you talk a little bit about it?

I would love to believe so. Concrete examples and I’m failing. I get these messages sometimes from the most unbelievable sweeties who wanna connect. I had these two sisters send me a video of them hula-hooping to show how they were little bad-asses unafraid of patriarchy and I cried for like ten minutes.

I think its more about all the folks who experience oppression in ways creating this space of tension to hegemonic gender identities or white supremacy or whatever else, for each other. Sometimes it’s about doing work that empowers someone to give themselves permission to do a big thing they want to do. I would love to think I helped some folks just completely go for it on walls, but I’m just happy if anyone did anything anywhere that made them feel tougher and safer or happier as a result of my work.

You recently did the cover for the upcoming AK Press book, Against the Fascist Creep by Alexander Reid Ross, who wrote the Trumpism column for It’s Going Down. You also have some art in the new Perspectives on Anarchist Theory. How did these projects come about? Are you planning on doing more art like this in the future for anarchist projects?

These projects came about through relationships and conversations. I plan on hopefully doing a million more. Right now I have two pieces I’m working on. One focuses on stopping police and prison violence against families, specifically mothers and youth. The other is for supporting survivors of sexual and domestic violence. I’m usually always happy to do big illustrative designs, especially if it’s about matristic resistance to fascism, and usually I have something that may already work. It’s just about finding space and balance within my own life.

Your recent work seems to have become much more straight forwardly radical. Was that always a part of your work, or has this grown over time?

I used to keep my more overtly political work and my Bonzo work separate to a paranoid level. Though the political work was all about vandalism and being in the streets and organizing with others, and my Bonzo work was always very political. I think you find this with a lot of folks actually. One day you wake up and realize the person who made all those police-brutality posters and one of your favorite outdoor enthusiasts are the same, and the two things look nothing like each other.

About two years ago, it was just too much of a stress to keep compartmentalizing and I stopped feeling the motivation that had led me to keep them so separate. It just turned into a huge personal betrayel to do so. For me, it was always this kinda fear that one community wouldn’t accept me, or I would get targeted more, as a result of graff or politics. The folks I work with in Portland are so wonderful, they made it safe to be both. It is one of the greatest reliefs to not keep it separate anymore.

Plus…I just wanted to use my own illustrative style for all of my favorite folks and projects/movements.

You’re created some anti-fascist posters and artwork as of late that has also incorporated a lot of your trademark use of plants, animals, and natural imagery. What is your take on fascist groups more and more appropriating these artistic forms, either Celtic or pagan imagery, or ecological aesthetics.

Many fascists movements have presented themselves as a return to traditional and ecological values. I think the incorporation of natural elements and imagined or real pagan imagery has been ever present in fascism. One of the earliest proponents of ecology was German scientist Ernst Haeckel (who is also credited with coining the term) who has been named by many academics as a key factor in the birth of the fascist ideology of the Nazi party in Germany.

Within the environmental movement, anti-civ, primitivism crew, I think you see a lot of fascism and white supremacy masquerading as radical or anarchist politics and it terrifies me. But fascism is always imagining itself as a radical project anyways, look at Alex Jones. You look at the work of Julius Evola, who was advocating for a return to traditionalism, heroic masculinity, and seeking a rebirth of greatness. He’s in there somehow smushing together the Holy Roman Empire with the Celtic Grail with Germany into one awful spiral, its almost indistinguishable from what you see coming out of a lot of the circles who are easily and readily accepted within anarchist spaces. They’re smooshing sacred geometry, Hindu practices, Stonehenge, and America into the same golden spiral.

There’s a paper, Ur-Fascism, by Umberto Eco detailing some of the eternal characteristics of fascist movements, which are present regardless of where and when that movement is. When looking at how fascism manifests in environmental and ecological movements you can see; the cult of return to an imagined traditionalism (not an actual living traditionalism as in Indigenous communities), the valorization of action for action sake as life is permanent warfare, an “other” or “difference” who has decayed this past strength, valor, and purity of the cult, and a regeneration through bloodletting as the only means to regain honor and vitality. Blood and Soil.

These folks have no interest in supporting Indigenous Sovereignty, as they’ve re-imagined themselves as the “true Indigenous peoples.” They have no interest in actively trying to organize against cis-hetero-patriarchy or white supremacy, because that entails being in active service to others, and at times being able to imagine alternatives to violence and militarism. They have no interest in actively developing deep and healthy relationships, of mutual respect, reciprocity, and responsibility because they can’t imagine how.

You know, we have DGR up here. And they’ve been long outed as some of the most transphobic piles of trash you could ever step in. That transphobia is inevitable in an ideology which valorizes militarism and mass murder and claims it is the only possible strategy. You can’t have that type of militarism without a hegemonic masculinity, which forces and then polices a toxic gender binary. Those folks not only advocate for carpet bombing cities of civilians, but say it is the one inevitable path. They’ve been banned from a lot of spaces which is so amazing to see, but I meet folks exactly like them who just happen to claim they’re not transphobic, but why is the carpet-bombing okay? When is it ever okay to mass murder? How is this anarchist?

“[Portland] is becoming a rich person’s playground and unrelenting stress, anxiety, and abuse for the rest of us.”

Anyone who tells you its inevitable that we HAVE to kill or let die millions of people to save the world, may as well go work for a pipeline company or in the Dakota oil fields.

The show Portlandia has put Portland in the minds of millions of people. While the show is often hilarious, what are your thoughts of the show presenting an image of the town to so many people?

For folks working here, that show is disruptive as hell, hated, maligned, and novelty-washes this city. Portland is not a good place for many folks. We have some of the most extraordinary white supremacist history (and present), we are the third most polluted city in the country, and we have extraordinary violence daily to our most vulnerable people. That show is helping keep PDX contrived as hell and helping to ensure that when folks talk about this city, they aren’t talkin about our openly Nazi police captain (Mark Kruger “The Claw”) or the huge cancer clusters around Warren Buffet’s military developer making drones (Precision CastParts).

There’s been a lot of action happening around housing in Portland, fights over rent control, targeting certain landlords, and the growth of various campaigns at things like Burgerville. You’ve also done some art for local groups towards this end. How would you describe Portland currently for most working and poor people? Is it getting worse and harder to get by? How are people fighting back?

This place is becoming a rich person’s playground and unrelenting stress, anxiety, and abuse for the rest of us. Its getting so impossible to survive here. Folks are getting evicted one after another, buildings are being demolished, our houseless population is growing as sweeps intensify. People are coming together in support of one another in the most extraordinary ways. I could never list them all. Groups have been organizing copwatches and direct aid (i.e. keeping folks stuff out of the dump) when there are sweeps of our encampments. We have two solidarity networks that organize around tenant rights and have escalating community campaigns to apply pressure for property owners or companies to honor the rights and needs of tenants, one of those also does labor campaigns.

We have people demanding clean-ups of our toxic hot spots where poor folks live and/or camp. We have folks creating native gardens. Letting people camp in their backyard. We have Black Lives Matter PDX challenging the cities policy and history of police brutality towards communities and individuals of color and constantly pushing for more accountable dialogues on racism, which in a gentrifying city, is invaluable. We have scholars like Walidah Imarisha (who just moved) constantly educating folks on this cities white supremacist origins and doing this amazing transformative work in prisons. We have Inter-Tribal groups out here demanding the right to clean air, food, and water, who are cleaning rivers, restoring traditional fishing sites, enforcing Treaty rights, protecting salmon. Right To Dream Too, a tent city which helps folks transition to more stable living has been going strong since 2011 right in the middle of downtown, and pushing a Houseless Bills of Rights. We have the Native American Youth and Family Services organizing huge housing programs for PDX’s urban Native population and just being a huge resource in a thousand other ways.

There’s an untold number of unbelievable people, working tirelessly out here to try to ensure that people in this city have the right to housing, food, water, and dignity. I think there are a lot of people out here challenging the city when it tells us “its developing.” People who are asking what is being developed, because it isn’t access to food, water, and housing. People who are challenging the cities narratives of progress, and what exactly is meant by that, and who is going to suffer for a few folks to get their progress. Its exhausting, inspiring, and terrifying all at once. I’ve been pushed out only a few times, and consider myself pretty lucky to have the housing I do now.

Drawing and creating great art is certainly a very needed skill in the anarchist movement. From websites, to flyers, to publications – we all need great images, art, and design to help grow and get ourselves out there. What do you think people should be doing in this regard that they aren’t already doing? How do you think our movement could incorporate art in a way that it isn’t currently doing now?

There are so many people in so many places creating work that helps to conceptualize our movements and inspire us and connect to others.

I think that a lot of the history of political art has conceptualized resistance as a purely reactive physical act of offense/or defense. I see a lot of that imagery as being the aesthetic of only one potential type of one potential resistance. And I’m there, I love it. I want a landlord or a cop to be afraid. But I look at someone like Erin Marie Konsmo’s work, who’s talking about reproductive justice as land rights and restoring Indigenous forms of justice as stopping colonial violence, or Demian DinéYazhi’ who’s working on these amazing No-Wave Indigenous Feminist pieces and showcasing queer relationships pre-colonization, Maz Atl who’s drawing women, life and food, and disappearing animals.

“I see a lot of anarchist aesthetic embracing hard lines, hard forms, sharp jutting angles, and its almost looking like architecture. I want to see art that looks like living worlds and people.”

And, I feel like sometimes only one very singular type of resistance is being valorized and showcased within anarchist aesthetic. And that dialogue can only go so far. The above are all folks who have such broad dialogues on what resistance can be and is. And the work is beautiful. Just undeniably lovely. I see a lot of anarchist aesthetic embracing hard lines, hard forms, sharp jutting angles, and its almost looking like architecture. I want to see art that looks like living worlds and people.

Dialogues and aesthetics of care, different and healthier ways of being in relationship to each other, family and mother’s resistance, of living traditions which pre-date and survive against colonization. These are all incredibly transformative dialogues, and I get bored of seeing resistance or anarchim only being conceptualized as a project of individualist or collective militancy. I want to definitely see more femme or feminized principle work being showcased. Work that’s focusing on care and love for each other. Acts of resistance which are extraordinary and powerful when they challenge how so many of our relationships to each other are structured or socialized through hegemonic masculinity, capitalism, white supremacy, all the other forms of abuse that are heaped onto folks.

When the dialogue and aesthetic which surround militant responses aren’t being weighted by care and love, and aren’t clearly marked as coming from responsibilities to defend families, food, water, self-determination, and land, its just going to reproduce militarism and patriarchy in our groups. Which I think we actually do find a lot of within predominately white anarchist spaces. A lot of folks are already out there doing this work, and its just not become as popularized or recognized as its going to have to be to create these widely transformative spaces we need.

Is there a sustainable way for an artist to make radical art, or any art for that matter, that is connected to a wider movement? Or do you think that it’s more sustainable to separate that from a more stable source of income that a ‘regular’ job would bring? Any tips for up and coming artists that want to do what they’re doing full time?

Hmmm, that’s a tough one. Even jobs that traditional payed your rent and food are being almost impossible to survive on. Art is kinda funny. There’s a lot of folks not coming from backgrounds which financially support them, who have found ways to be able to work on art as their means of survival. I think its all about how you personally, are able to pay your rent and meet your basic needs. Whether that’s art, a job, a hustle, or a racket.

Outside of just inheriting a bunch of money, I don’t really know of any simple path to being able to support yourself on just art work, especially without massive community support. Not letting yourself be pressured into believing that your work has no value (or you yourself have no value) if it doesn’t support you, or falling into purity politics self-loathing if it does, is what I think is most important. I try to see art as resiliency and connection, and sometimes a way to buy a bunch of burritos and chill with the folks I respect and love.

What are some other artists out there that you would encourage people to check out? What makes you excited about them?

A lot of people. But I’m just going to talk about some of the folks who inspire me. All of the women of Few and Far, GATS, Deadeyes, all of PTV and BDS, everyone who’s already been mentioned above, Entangled Roots, Joshua Mays, Sara Siestreem, Pancho Pescador, and just so so many folks. For writers; Vandana Shiva, Evelyn Reed, Rhoda Reddock, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, Marie Mies, Carolyn Merchant, and Sylvia Frederici.

The thing that inspires me about these people is they are all creating amazing stories and working on incredibly transformative dialogues of how we can be in healthier relationship with ourselves, to others, and land. The folks I personally know are some of the nicest people you will ever meet too.

What kinds of projects do you have coming up that people should put on their radar? How can people support your work?

As far as for myself, I have two projects I’m excited about. The first being the completion of an illustrated direct action alphabet, I’m almost done with all of those letters, and it will be freely available for use. The second being an illustrated book under the title, All Our Mothers Resisted Fascism. This is still heavily in the works, but I’m hoping to be able to collaborate with a bunch of folks I respect to create a huge illustrative and narrative publication on women’s and family resistance to colonialism and fascism. To share those stories that end up as footnotes or are presented as merely being in support of men’s work.

As cis-hetero-patriarchy works to eradicate women’s power, create and enforce strict gender roles, and define women and nature as passive resources subject to domination and appropriation, histories of resistance neglect women’s participation and project men into leading roles and visibility.

As cis-hetero-patriarchy works to eradicate women’s power, create and enforce strict gender roles, and define women and nature as passive resources subject to domination and appropriation, histories of resistance neglect women’s participation and project men into leading roles and visibility. Patriarchal bias in social and political histories conceive of resistance as heroic and individualistic male orientated projects and further reinforce behaviors and ideologies which lead to erasure and violence against women, queer, and gender non-conforming people’s participation in resistance movements. I want to work on a big illustrated book with a bunch of folks I love and just share these stories and histories.

Support and Buy N.o. Bonzo’s Work Here

Tumblr

Facebook

Instagram

Recent Comments